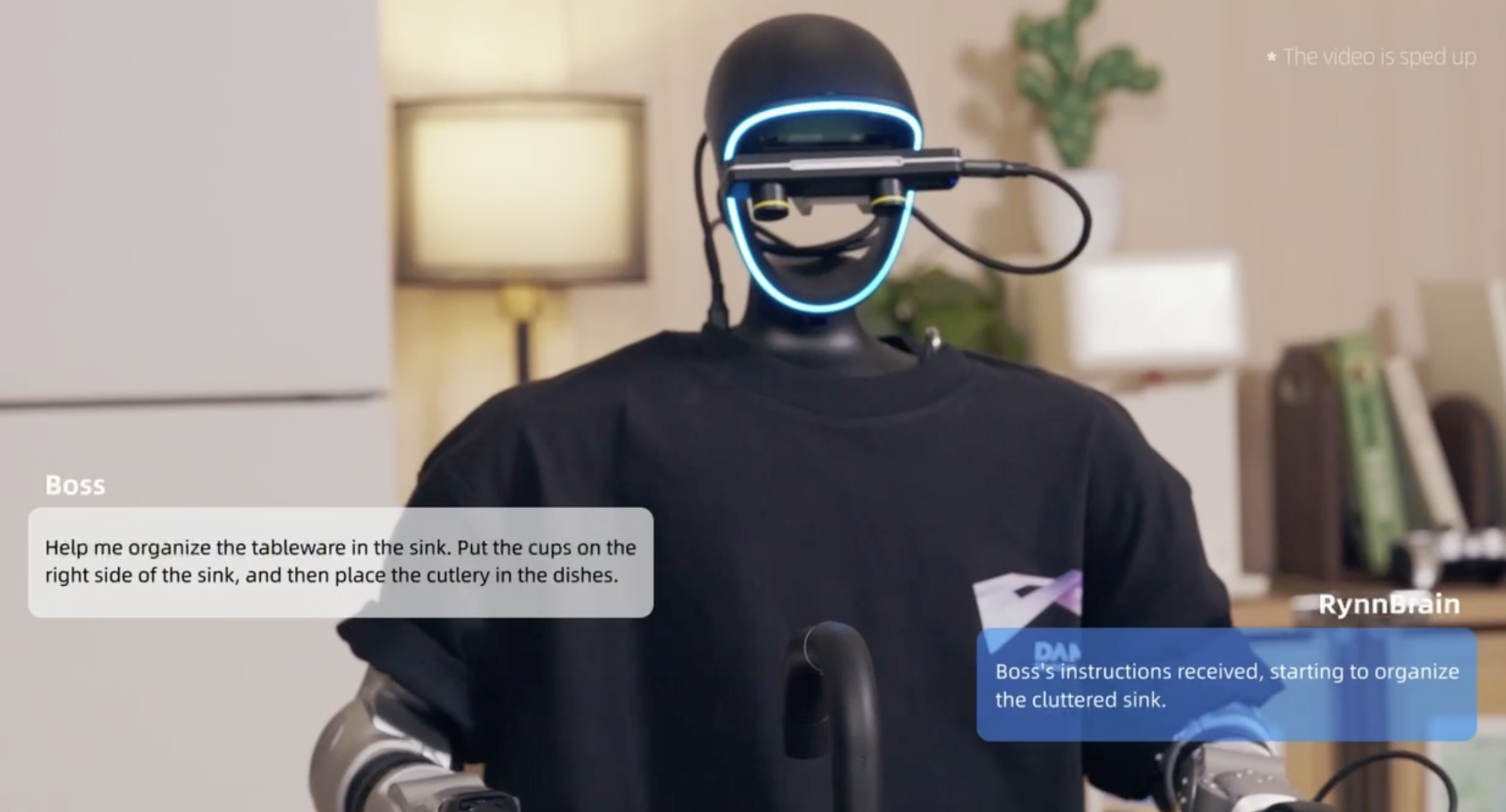

Alibaba has entered the race to build AI that powers robots, not just chatbots. The Chinese tech giant this week unveiled RynnBrain, an open-source model designed to help robots perceive their environment and execute physical tasks.

The move signals China’s accelerating push into physical AI as ageing populations and labour shortages drive demand for machines that can work alongside—or replace—humans. The model positions Alibaba alongside Nvidia, Google DeepMind, and Tesla in the race to build what Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang calls “a multitrillion-dollar growth opportunity.”

Unlike its competitors, however, Alibaba is pursuing an open-source strategy—making RynnBrain freely available to developers to accelerate adoption, similar to its approach with the Qwen family of language models, which rank among China’s most advanced AI systems.

Video demonstrations released by Alibaba’s DAMO Academy show RynnBrain-powered robots identifying fruit and placing it in baskets—tasks that seem simple but require complex AI governing object recognition and precise movement.

The technology falls under the category of vision-language-action (VLA) models, which integrate computer vision, natural language processing, and motor control to enable robots to interpret their surroundings and execute appropriate actions.

Unlike traditional robots that follow preprogrammed instructions, physical AI systems like RynnBrain enable machines to learn from experience and adapt behaviour in real time. This represents a fundamental shift from automation to autonomous decision-making in physical environments—a shift with implications extending far beyond factory floors.

From prototype to production

The timing signals a broader inflexion point. According to Deloitte’s 2026 Tech Trends report, physical AI has begun “shifting from a research timeline to an industrial one,” with simulation platforms and synthetic data generation compressing iteration cycles before real-world deployment.

The transition is being driven less by technological breakthroughs than by economic necessity. Advanced economies face a stark reality: demand for production, logistics, and maintenance continues rising while labour supply increasingly fails to keep pace.

The OECD projects that working-age populations across developed nations will stagnate or decline over the coming decades as ageing accelerates.

Parts of East Asia are encountering this reality earlier than other regions. Demographic ageing, declining fertility, and tightening labour markets are already influencing automation choices in logistics, manufacturing, and infrastructure—particularly in China, Japan, and South Korea.

These environments aren’t exceptional; they’re simply ahead of a trajectory other advanced economies are likely to follow.

When it comes to humanoid robots specifically—machines designed to walk and function like humans—China is “forging ahead of the U.S.,” with companies planning to ramp up production this year, according to Deloitte.

UBS estimates there will be two million humanoids in the workplace by 2035, climbing to 300 million by 2050, representing a total addressable market between $1.4 trillion and $1.7 trillion by mid-century.

The governance gap

Yet as physical AI capabilities accelerate, a critical constraint is emerging—one that has nothing to do with model performance.

“In physical environments, failures cannot simply be patched after the fact,” according to a World Economic Forum analysis published this week. “Once AI begins to move goods, coordinate labour or operate equipment, the binding constraint shifts from what systems can do to how responsibility, authority and intervention are governed.”

Physical industries are governed by consequences, not computation. A flawed recommendation in a chatbot can be corrected in software. A robot that drops a part during handover or loses balance on a factory floor designed for humans causes operations to pause, creating cascading effects on production schedules, safety protocols, and liability chains.

The WEF framework identifies three governance layers required for safe deployment: executive governance setting risk appetite and non-negotiables; system governance embedding those constraints into engineered reality through stop rules and change controls; and frontline governance giving workers clear authority to override AI decisions.

“As physical AI accelerates, technical capabilities will increasingly converge, but governance will not,” the analysis warns. “Those that treat governance as an afterthought may see early gains, but will discover that scale amplifies fragility.”

This creates an asymmetry in the US-China competition. China’s faster deployment cycles and willingness to pilot systems in controlled industrial environments could accelerate learning curves.

However, governance frameworks that work in structured factory settings may not translate to public spaces where autonomous systems must navigate unpredictable human behaviour.

Early deployment signals

Current deployments remain concentrated in warehousing and logistics, where labour market pressures are most acute. Amazon recently deployed its millionth robot, part of a diverse fleet working alongside humans. Its DeepFleet AI model coordinates this massive robot army across the entire fulfilment network, which Amazon reports will improve travel efficiency by 10%.

BMW is testing humanoid robots at its South Carolina factory for tasks requiring dexterity that traditional industrial robots lack: precision manipulation, complex gripping, and two-handed coordination.

The automaker is also using autonomous vehicle technology to enable newly built cars to drive themselves from the assembly line through testing to the finishing area, all without human assistance.

But applications are expanding beyond traditional industrial settings. In healthcare, companies are developing AI-driven robotic surgery systems and intelligent assistants for patient care.

Cities like Cincinnati are deploying AI-powered drones to autonomously inspect bridge structures and road surfaces. Detroit has launched a free autonomous shuttle service for seniors and people with disabilities.

The regional competitive dynamic intensified this week when South Korea announced a $692 million national initiative to produce AI semiconductors, underscoring how physical AI deployment requires not just software capabilities but domestic chip manufacturing capacity.

NVIDIA has released multiple models under its “Cosmos” brand for training and running AI in robotics. Google DeepMind offers Gemini Robotics-ER 1.5. Tesla is developing its own AI to power the Optimus humanoid robot. Each company is betting that the convergence of AI capabilities with physical manipulation will unlock new categories of automation.

As simulation environments improve and ecosystem-based learning shortens deployment cycles, the strategic question is shifting from “Can we adopt physical AI?” to “Can we govern it at scale?”

For China, the answer may determine whether its early mover advantage in robotics deployment translates into sustained industrial leadership—or becomes a cautionary tale about scaling systems faster than the governance infrastructure required to sustain them.

(Photo by Alibaba)

See also: EY and NVIDIA to help companies test and deploy physical AI

Want to learn more about AI and big data from industry leaders? Check outAI & Big Data Expo taking place in Amsterdam, California, and London. The comprehensive event is part of TechEx and is co-located with other leading technology events, clickhere for more information.

AI News is powered by TechForge Media. Explore other upcoming enterprise technology events and webinars here.