Department of Dermatology, Affiliated Central Hospital of Shenyang Medical College, Shenyang, Liaoning, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xiaodong Li, Department of Dermatology, Affiliated Central Hospital of Shenyang Medical College, 5 Nanqi West Road, Shenyang, Liaoning, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected] Yang Han, Department of Dermatology, Affiliated Central Hospital of Shenyang Medical College, 5 Nanqi West Road, Shenyang, Liaoning, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a rare form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Because the etiology and pathogenesis remain unclear and the cutaneous manifestations are highly variable, no definitive diagnostic criteria have been established. As a result, the risk of diagnostic errors and missed diagnoses is common in clinical practice. This report describes the case of a 64-year-old woman with facial CRDD that initially misdiagnosed as sporotrichosis. This case broadens the known clinical spectrum of CRDD and underscores the importance of careful differential diagnosis to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Rosai-Dorfman disease, sporotrichosis, histiocytic diseases, sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, emperipolesis

Introduction

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is a rare form of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, characterized by the accumulation of histiocytes within lymph node sinuses and various extranodal tissues. The disease most commonly affects the skin and lymph nodes. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a rare cutaneous variant confined to the skin. Roughly 10% of RDD patients have skin lesions, and only 3% show isolated cutaneous involvement. CRDD typically manifests as solitary or multiple nodules and plaques, which present clinically as yellowish-red to brown or violaceous papules, most frequently affecting the face.1,2 Diagnosis of CRDD relies on a combination of clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical features and is often challenging because CRDD can closely resemble other dermatologic conditions, including xanthoma, Kaposi sarcoma, cutaneous lymphoma, tuberculosis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.3 This report describes an uncommon presentation of CRDD with clinical features that initially misdiagnosed as sporotrichosis, a manifestation rarely reported in the literature.

Case Report

A 64-year-old woman presented with a solitary erythematous nodule on the right cheek that had developed four months earlier without an identifiable precipitating factor. The nodule gradually enlarged, forming an erythematous plaque that ulcerated and developed a thick, greasy, yellowish-white crust (Figure 1). It was asymptomatic, with no associated pain or pruritus. Histopathological examination revealed epidermal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation in the dermis, with dense inflammatory infiltrates composed predominantly of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils (Figure 2). Both Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and acid-fast stains were negative. Nevertheless, sporotrichosis remained in the differential diagnosis because the patient resided in northern China, an area highly endemic for the disease.4 Based on the presence of a progressively enlarging, ulcerated, crusted erythematous plaque and the corresponding histopathological findings of epidermal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia accompanied by granulomatous inflammation, sporotrichosis was established as the initial diagnosis, and empirical antifungal therapy with itraconazole (200 mg/day) was initiated. However, after two months of treatment, the lesion continued to enlarge and protrude above the skin surface (Figure 3). Re-examination of the original biopsy specimens, including additional sectioning and staining, revealed diffuse dermal infiltration with numerous histiocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils and some plasma cells. Characteristic emperipolesis was also observed (Figure 4A and B). At immunohistochemical analysis, the large histiocytes were positive for CD68 and S100 but negative for CD1a and CD207 (Figure 5A–D). The diagnosis of CRDD was established based on these findings. The patient subsequently underwent complete surgical excision of the lesion and was monitored for two months postoperatively, during which no recurrence was observed.

| Figure 1 Solitary erythematous plaque on the right cheek covered with a thick, greasy, yellowish-white crust. |

| Figure 2 Biopsy specimen showing epidermal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation in the dermis, with dense inflammatory infiltrates composed predominantly of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils (hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×25). |

| Figure 3 Reddish-brown plaque on the right cheek overlain by a pinkish, exophytic mass with a yellowish-brown crust. |

| Figure 4 (A) Histological examination of the resected specimen shows diffuse dermal infiltration composed of histiocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils and some plasma cells (hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×25). (B) Emperipolesis is observed within the histiocytes as indicated by the red arrow (hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×400). |

Figure 5 Immunohistochemical staining showing histiocytes positive for (A) S100 and (B) CD68 (×25 magnification) and negative for (C) CD1a and (D) CD207 (×25 magnification). |

Discussion

RDD, first described by Rosai and Dorfman in 1969, was originally termed sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. Subsequent studies have found that approximately 40% of cases exhibit extranodal involvement, with the skin being among the most commonly affected sites.5 CRDD is a distinct subtype characterized by lesions confined to the skin without systemic manifestations and accounting for approximately 3% of all RDD cases.5,6 The etiology and pathogenesis of CRDD remain incompletely understood. Evidence of clonal proliferation in some cases suggests a potential neoplastic component.7 Other studies have proposed associations with immune dysregulation, infectious agents, and genetic factors.8,9 CRDD may occur as an isolated condition or in conjunction with autoimmune disorders and malignancies.10–12

CRDD can develop at any age, with a mean onset of approximately 45 years, and exhibits a slight female predominance.6 Its clinical manifestations are remarkably diverse, presenting as papules, nodules, plaques, or other morphologic variants.6,13 Typical lesions are firm, reddish-yellow papules or nodules that may show surface scaling and, occasionally, tenderness.1,14 In certain cases, CRDD presents as a tumor-like exophytic mass, particularly on the face, and most closely resembling other cutaneous neoplasms.5,14 Rarely, lesions exhibit an acral distribution involving the palms and soles. This presentation is particularly uncommon and prone to misdiagnosis as other dermatologic conditions.15

Diagnosis relies primarily on histopathologic evaluation, which typically reveals a dense dermal infiltrate consisting of histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.13 The hallmark histological feature is emperipolesis: the engulfment of intact inflammatory cells within histiocytes.1,5 However, emperipolesis is not universally observed and might only be detected through serial sectioning and meticulous microscopic examination,12,14 making diagnosis occasionally challenging.12 Immunohistochemical analysis is also essential for diagnostic confirmation, as the characteristic histiocytes show positivity for S100 protein and CD68, but are negative for Langerhans cell markers such as CD1a and langerin.5,6,13

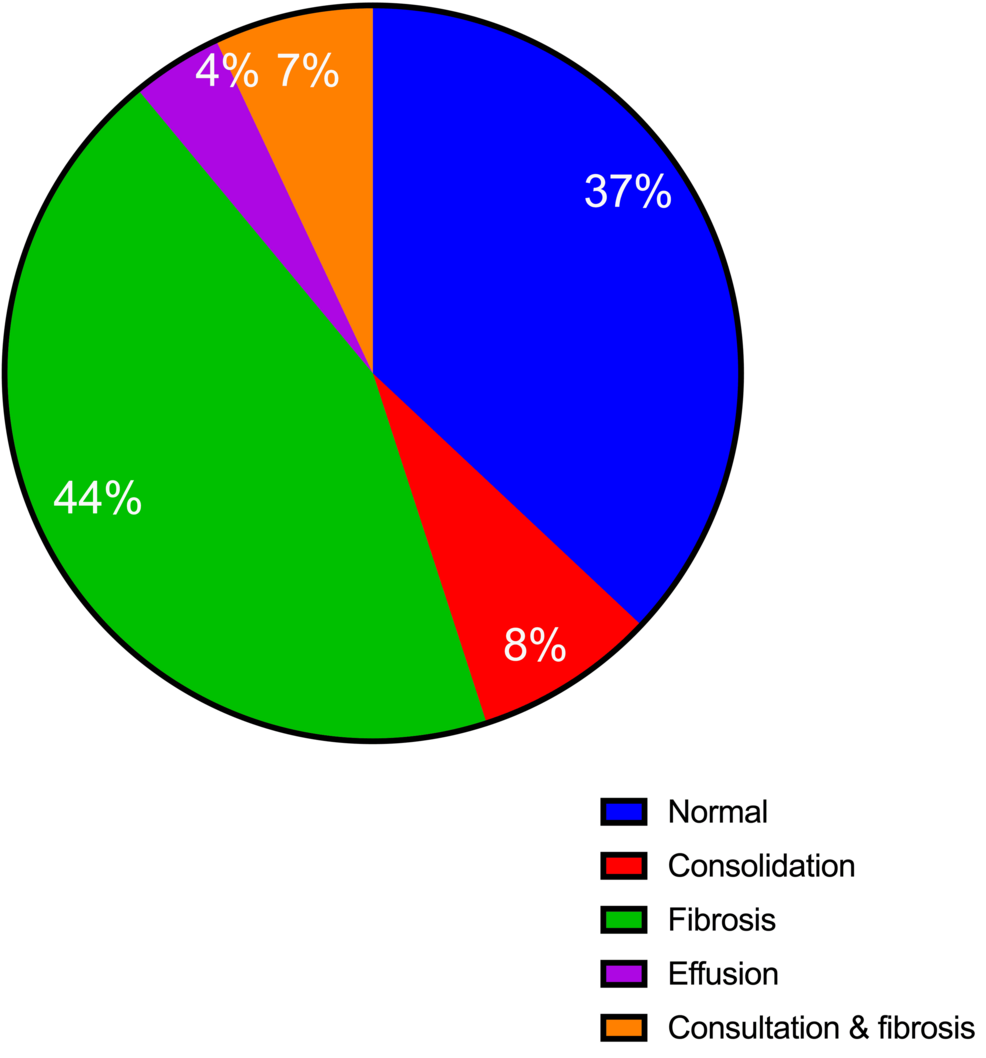

In keeping with the rarity and highly variable clinical presentation of CRDD, the absence of pathognomonic clinical features, and the lack of definitive diagnostic criteria, histopathologic findings may also be atypical at times, leading to greater risk of clinical misdiagnosis.13–15 A summary of reported misdiagnosed cases is presented in (Table 1).

| Table 1 Summary of Previously Reported Cases of CRDD Initially Misdiagnosed as Other Dermatologic Conditions |

A comprehensive review of previously misdiagnosed cases indicates that CRDD lacks specific clinical manifestations and often mimics various other dermatologic conditions. Most laboratory findings in affected patients fall within normal limits, leading clinicians to initially consider more common diseases. Histopathologic diagnosis of CRDD can also be challenging. In many cases, multiple biopsy sections are required before the characteristic feature of emperipolesis becomes evident, representing a principal cause of misdiagnosis.

In the present case, the cutaneous nodule initially observed on the patient’s face closely resembled sporotrichosis. However, over the course of several months, the lesion grew rapidly into a large, tumor-like mass several centimeters in diameter. Failure of the initial histopathologic examination to detect emperipolesis probably contributed to the incorrect preliminary diagnosis and the inappropriate prescription of antifungal therapy. Only after subsequent resection and deeper sectioning of the tissue were more characteristic histopathologic features of CRDD detected, after which the diagnosis was further confirmed by comprehensive immunohistochemical analysis. A limitation of this study is the lack of fungal culture for sporotrichosis. Given that sporotrichosis culture yield highly depends on specimen type,23 superficial culture was unfeasible as no purulent discharge or crusts were present 7 days post initial biopsy. The patient refused repeated deep tissue sampling and demanded empirical treatment, thus failing to further complete deep fungal culture. As the gold standard for sporotrichosis diagnosis, missing this test cannot completely rule out concurrent fungal infection, which affects the certainty of diagnosis to a certain extent. Particularly challenging cases may require repeat biopsy or deeper tissue sampling to identify the hallmark features of the disease.12 Establishing a standardized diagnostic workflow would therefore be instrumental in improving diagnostic accuracy and minimizing misdiagnosis of CRDD.9

Treatment of CRDD should be individualized according to the clinical presentation, as no standardized therapeutic guidelines currently exist.24,25 For patients with mild or asymptomatic disease, a watch-and-wait approach is often appropriate because of the benign and occasionally self-limiting nature of CRDD, with some cases resolving spontaneously.5,25 Surgical excision remains the most commonly employed intervention, particularly for solitary or symptomatic lesions.24,26 In the present case, complete surgical resection was performed, and no recurrence was observed during follow-up. Pharmacologic therapies have also been used in selected cases, including corticosteroids, retinoids, thalidomide, methotrexate, and dapsone, among others.27

Conclusion

In clinical practice, when CRDD is suspected, thorough evaluation is essential to ensure diagnostic accuracy and appropriate management. A detailed medical history, assessment for potential comorbidities, and prompt histopathologic and immunohistochemical examinations are critical for establishing the correct diagnosis. Additionally, fungal culture is critical when fungal infection is included in the differential diagnosis. Such vigilance helps prevent misdiagnosis or delayed recognition, thereby avoiding inappropriate treatment and potential disease progression.

Ethics Statement

Affiliated Central Hospital of Shenyang Medical College approved to publish the case details.

Consent Statement

The patient has provided written informed consent for the publication of their case details and accompanying images. We ensure adherence to ethical standards, respect patient privacy, and conduct our research and publication in strict accordance with relevant guidelines.

Funding

No funding has been gathered for this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Altamimi NM, Li V, Kahn H, Shaikh G. Rosai-Dorfman disease case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2025;17(1):299–303. doi:10.1159/000546278

2. Bielach – Bazyluk A, Serwin AB, Pilaszewicz – Puza A, Flisiak I. Cutaneous Rosai – Dorfman disease in a patient with late syphilis and cervical cancer – case report and a review of literature. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12895-020-00115-w

3. St. Claire K, Edriss M, Potts GA. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report. Cureus. 2023. doi:10.7759/cureus.39617

4. Li J, Mou J, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Mou P. Difference analysis of cutaneous sporotrichosis between different regions in China: a secondary analysis based on published studies on sporotrichosis in China. Ann Transl Med. 2023;11(4):180. doi:10.21037/atm-23-448

5. Zhang P, Liu F, Cha Y, Zhang X, Cao M. Self-limited primary cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review. CCID. 2021;14:1879–1884. doi:10.2147/CCID.S343815

6. Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166–173. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2019.02.004

7. Bruce-Brand C, Schneider JW, Schubert P. Rosai-Dorfman disease: an overview. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73(11):697–705. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206733

8. Tan Y, Zhou Y, Zhan Y, Luo S, Liu Y, Zhang G. Case of generalized tumor-type Rosai–Dorfman disease with sarcoidosis-like histological features and IgG4-positive plasma cells. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43(1):e9–e12. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001724

9. Kalakutskiy NV, Baranova IB, Ovsepian TN, Ribakova MG, Kasimova ND. Non-Langengars type of sinus histiocytosis with maxillofacial skin lesions (Rosai—Dorfman disease). Clinical case description. Stomat. 2021;100(3):90. doi:10.17116/stomat202110003190

10. Subhadarshani S, Kumar T, Arava S, Gupta S. Rosai-Dorfman disease with cutaneous plaques and autoimmune haemolytic anemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(11):e231927. doi:10.1136/bcr-2019-231927

11. Shelley AJ, Kanigsberg N. A unique combination of Rosai-Dorfman disease and mycosis fungoides: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Reports. 2018;6:2050313X18772195. doi:10.1177/2050313X18772195

12. Kipfer SL, Samycia M, Shiau CJ. Emergence of cutaneous Rosai–Dorfman disease during immunosuppressive treatment of follicular B-cell lymphoma: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Reports. 2021;9:2050313X211046455. doi:10.1177/2050313X211046455

13. Sampaio R, Silva L, Catorze G, Viana I. Cutaneous Rosai–Dorfman disease: a challenging diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(2):e239244. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239244

14. Hur K, Hong JY, Kim KH, et al. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: dermoscopic findings with successful surgical treatment. Ann Dermatol. 2023;35(Suppl 2):S287. doi:10.5021/ad.22.071

15. Dsouza V, Jayaraman J, Loganathan E, et al. Cutaneous Rosai–Dorfman disease mimicking granulomatous dermatoses: a rare case report. Pediatric Dermatol. 2025:

16. Stefanato CM, Ellerin PS, Bhawan J. Cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease) presenting clinically as vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(5):775–778. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.119565

17. Liu G, Wang H, Yang Z, Tang T, Zhang S. Is it a metastatic disease: a case report and new understanding of Rosai–Dorfman disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38(6):e72–e76. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000510

18. El-Kamel M, Selim M, Gawad MA. A new presentation of isolated cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: eruptive xanthoma-like lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86(2):158. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_540_17

19. D’Agostino GM, Giannoni M, Rizzetto G, et al. Cutaneous Rosai–Dorfman disease in a 42-year-old woman: a rare case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2021;30(2). doi:10.15570/actaapa.2021.22

20. Zghal M, Makni S, Saguem I, et al. Primary cutaneous Rosai–Dorfman–destombes disease with features mimicking IgG4‐related disease: a challenging case report and literature review. Aust J Dermatol. 2022;63(3):372–375. doi:10.1111/ajd.13869

21. Gillam J, Desai R, Louie RJ, et al. Cutaneous Rosai–Dorfman disease with MAP2K1 mutation, initially mimicking an infection with parasitized histiocytes. J Cutan Pathol. 2024;51(12):942–947. doi:10.1111/cup.14700

22. Amir B, Amir A, Sheikh S. A rare case of facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease clinically mimicking basal cell carcinoma followed by multiple myeloma after 2 years. JMedLife. 2024;17(2):239–241. doi:10.25122/jml-2023-0337

23. Hay R, Denning DW, Bonifaz A, et al. The diagnosis of fungal neglected tropical diseases (Fungal NTDs) and the role of investigation and laboratory tests: an expert consensus report. TropicalMed. 2019;4(4):122. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed4040122

24. Touati MD, Omry A, Ferjaoui W, Haloui N, Gargouri F, Khalifa MB. Diagnostic consideration of lipoma-like lesion: a case report of primary cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Int J Surg Case Reports. 2024;117:109475. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2024.109475

25. Deen IU, Chittal A, Badro N, Jones R, Haas C. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease- A review of diagnostic testing and management. J Commun Hospital Internal Med Perspectives. 2022;12(2):18–22. doi:10.55729/2000-9666.1032

26. Mohaghegh F, Saber M, Rajabi P, Sohrabi H. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a report of 2 cases and a review of recent literature (2018–2023). Case Rep Dermatol. 2025;17(1):204–223. doi:10.1159/000546382

27. Dhrif O, Litaiem N, Lahmar W, Fatnassi F, Slouma M, Zeglaoui F. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a systematic review and reappraisal of its treatment and prognosis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316(7):393. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-02982-6