Picture this: it’s 2003, and you’re a medical student in Brazil. You’re memorizing hundreds of diseases, but chikungunya isn’t one of them. Your textbook might mention it in a footnote—”rare African virus, sporadic outbreaks, not clinically significant.”

Fast forward to 2014. Brazilian hospitals are overwhelmed. People are flooding emergency rooms with sky-high fevers and joint pain so severe they can’t walk. Doctors are frantically Googling “chikungunya symptoms” because they’ve never seen a case.

What happened in those eleven years is one of the most dramatic disease spreads in modern history.

And it’s still happening.

The Explosion Nobody Saw Coming

Dr. Ramirez, an epidemiologist in São Paulo, remembers the panic clearly.

“We went from zero cases ever to hundreds of thousands in months,” she told me. “People thought it was dengue at first. Same mosquitoes, similar symptoms. But the joint pain—my God, the joint pain was different. People were crying in the waiting room.”

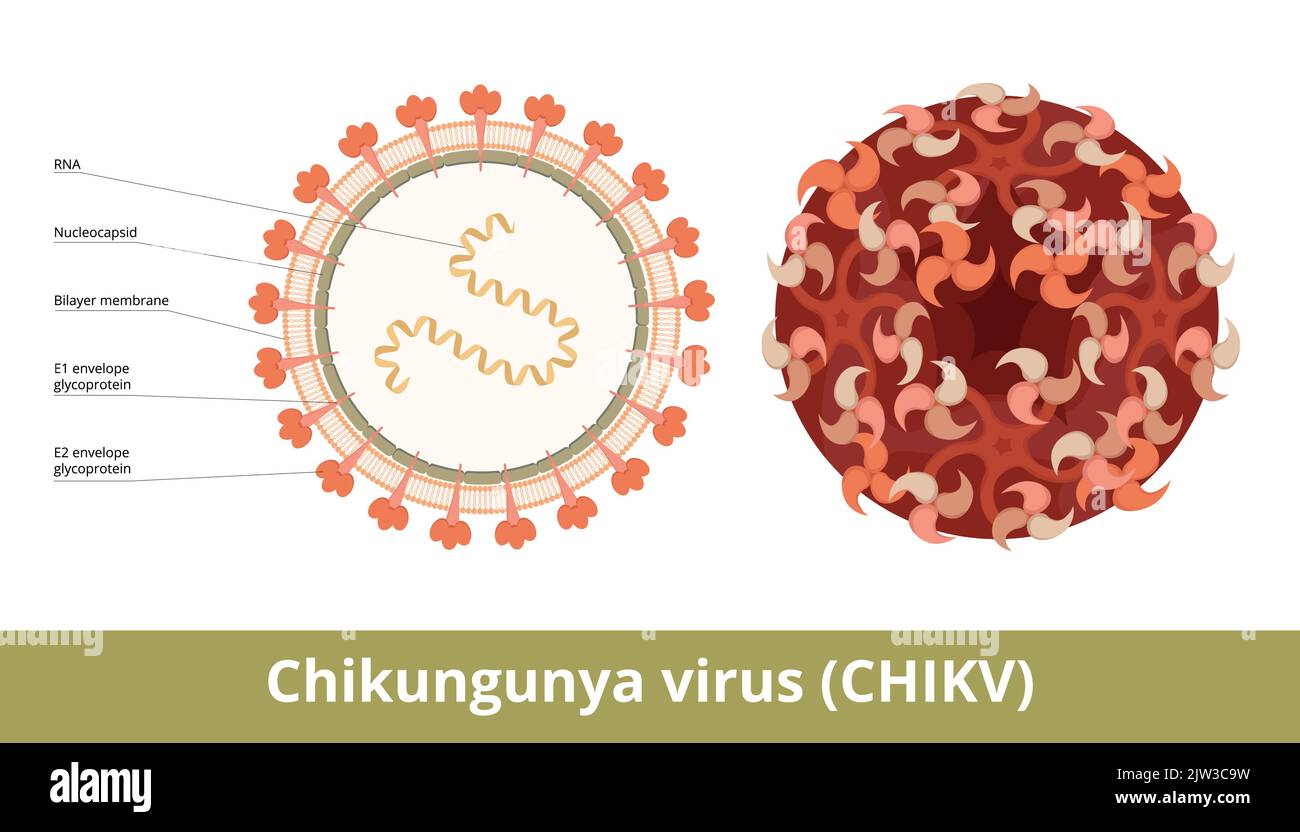

Chikungunya means “that which bends up” in an East African language. When you see patients hunched over, unable to straighten their backs because every joint is screaming, you understand why.

The virus was first identified in Tanzania in 1952. For fifty years, it stayed mostly in Africa and Southeast Asia, causing small, manageable outbreaks. Then 2004 hit.

The virus exploded across the Indian Ocean islands. Kenya. India. Indonesia. Italy—yes, Europe got cases. By 2013, it crossed the Atlantic and invaded the Americas.

Today? Over 110 countries. Millions infected. And it’s not slowing down.

The Worst Part? There’s No Fix

Here’s what keeps me up at night about chikungunya: we’re completely defenseless against it.

No antiviral drugs. No widely available vaccine. No way to prevent the chronic joint pain that ruins lives.

I spoke with Sandra, a 38-year-old teacher from Colombia who got infected in 2015.

“The fever lasted four days,” she said. “But my knees? My wrists? They hurt for three years. THREE YEARS. I couldn’t write on the blackboard. I couldn’t play with my kids. Some days I couldn’t button my shirt.”

Research shows 30-40% of chikungunya patients still have joint pain a year after infection. Some never fully recover.

Imagine: one mosquito bite, and your life changes forever.

The Daytime Assassins

Most people know about malaria mosquitoes that bite at night. Bed nets protect you. Simple.

Chikungunya mosquitoes laugh at your bed nets.

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus—the same striped demons that spread dengue and Zika—hunt during the day. Morning coffee on your patio? They’re there. Afternoon walk? They’re waiting. Kids playing outside after school? Prime feeding time.

Dr. Chen, a vector control expert in Singapore, explained why they’re so effective.

“These mosquitoes evolved alongside humans,” he said. “They breed in our flower pots, our discarded cups, our clogged gutters. They live in our homes. They’ve adapted to bite us when we’re most active and least protected.”

And they don’t need much water. A bottle cap. A leaf holding raindrops. That’s enough for dozens of larvae.

The Symptoms That Fool Doctors

Chikungunya is a master of disguise.

You get bitten. Three to seven days later, boom—high fever hits. Maybe 103°F, 104°F. You feel like death.

Then come the joints. Wrists, ankles, knees, fingers—often both sides of your body at once. The pain is intense, sharp, debilitating.

You might get a rash. Headache. Muscle aches. Nausea.

Sounds like dengue, right? Or Zika. Or even a bad flu.

That’s the problem. In areas where multiple diseases circulate, diagnosing chikungunya requires lab tests many clinics don’t have.

“I’ve seen patients treated for dengue for weeks before someone finally tests for chikungunya,” Dr. Patel, an infectious disease specialist in Mumbai, told me. “By then, they’re deep into chronic joint pain.”

The fever usually breaks in a few days. Most people think they’re recovering.

Then the joint pain intensifies.

“It’s like your body is playing a cruel joke,” Sandra said. “The fever’s gone, you think ‘okay, I’m getting better,’ and then your joints hurt worse than ever.”

Why It’s Spreading Like Wildfire

Climate change is handing chikungunya mosquitoes new territory on a silver platter.

Cities that were too cold for Aedes mosquitoes twenty years ago? Perfect habitat now. Southern Europe. Parts of the United States. Even areas of China and Japan that never had these mosquitoes are seeing them establish populations.

Urbanization helps too. Every new city, every expanding slum creates thousands of mosquito breeding sites. Construction materials holding water. Discarded tires. Poor drainage.

And international travel? That’s the express elevator for viruses.

An infected person boards a plane in Bangkok, lands in Mexico City twelve hours later. Local mosquitoes bite them. Boom—chikungunya is now in Mexico.

“We tracked one outbreak back to a single infected traveler,” Dr. Ramirez said. “One person. Within two months, 3,000 cases.”

What You Can Actually Do

The good news—and yes, there is some—is that prevention works. You just have to actually do it.

Destroy mosquito breeding sites religiously:

Walk your property every week. Empty anything holding water. Flower pots, buckets, pet bowls, gutters, tarps. If it can hold a teaspoon of water, dump it.

“People think I’m paranoid,” Jorge, a chikungunya survivor in Panama, told me. “But I check my yard twice a week now. I’m not going through that again.”

Protect your skin during daylight hours:

Long, light-colored clothing. Insect repellent with DEET, IR3535, or icariin. Window screens without holes. Mosquito coils indoors.

Yes, it’s annoying. Yes, repellent is sticky. Do it anyway.

Know the warning signs:

Sudden high fever plus severe joint pain, especially if you’re in or recently visited an affected area. Get tested for both chikungunya and dengue—the treatment considerations differ.

Don’t take aspirin or ibuprofen until dengue is ruled out. These can cause dangerous bleeding if you actually have dengue.

The Future We’re Facing

Two chikungunya vaccines recently got approved in some countries. That’s progress.

But they’re not widely available. Most of the world can’t access them. And even when they become available, vaccinating billions of at-risk people will take years.

Meanwhile, the virus keeps spreading.

Climate models predict Aedes mosquitoes will expand their range significantly over the next decade. More cities. More countries. More people at risk.

“We’re watching it happen in real-time,” Dr. Chen said. “And we’re not moving fast enough to stop it.”

Sandra has finally recovered. Four years after that mosquito bite, her joints don’t hurt anymore.

“But I’m different now,” she said. “I live in fear of mosquitoes. I check every corner of my house. I warn everyone. Because chikungunya isn’t just a disease you get and forget. It changes you.”

That’s the thing about chikungunya. It’s not just the acute illness. It’s the chronic pain, the missed work, the inability to hold your child, the years of suffering.

All from one bite.

The question isn’t whether chikungunya will continue spreading. It will.

The question is whether we’ll take it seriously before it reaches your neighborhood.

Frequently Asked Questions About Chikungunya

Q: What exactly is chikungunya? Chikungunya is a viral disease transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes that causes sudden high fever and severe, often debilitating joint pain. The name means “that which bends up” in the Kimakonde language, describing how victims hunch over from pain. First identified in Tanzania in 1952, it’s now found in 110+ countries worldwide.

Q: How do people get infected? Through bites from infected Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus mosquitoes—the same species that spread dengue and Zika. These mosquitoes bite during daylight hours, particularly early morning and late afternoon. There’s no direct person-to-person transmission except rare cases where infected mothers pass it to babies during childbirth.

Q: What makes chikungunya different from other mosquito diseases? The hallmark is severe joint pain that can become chronic. While dengue and Zika also cause fever and aches, chikungunya’s joint pain is typically more intense and persistent. 30-40% of patients experience joint pain lasting months or years after the initial infection—something rarely seen with other arboviral diseases.

Q: What are the symptoms and when do they appear? Symptoms appear 4-8 days after the bite: sudden high fever (often 102-104°F), severe joint pain affecting multiple joints (wrists, knees, ankles, fingers), headache, muscle pain, rash, nausea, and fatigue. The acute phase lasts 2-3 days, but joint pain often persists or intensifies even after fever resolves.

Q: Is there a cure or treatment? No specific antiviral treatment exists. Doctors can only treat symptoms: fever reducers, pain medications, rest, and fluids. Aspirin and NSAIDs must be avoided initially until dengue is ruled out due to bleeding risks. For chronic joint pain, treatment includes physical therapy and long-term pain management.

Q: Can chikungunya be fatal? Rarely. Most people recover from the acute illness, though joint pain may persist. Deaths are uncommon but can occur in vulnerable populations: newborns infected during delivery, elderly patients, and those with underlying health conditions. Complications affecting the heart, eyes, or nervous system occasionally occur.

Q: Are vaccines available? Two vaccines have recently received approval in some countries, but they’re not yet widely available globally. WHO is reviewing data for broader recommendations. For now, most people worldwide cannot access chikungunya vaccines, making prevention through mosquito control and bite avoidance critical.

Q: Where is chikungunya found today? In 110+ countries across Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Europe. Originally limited to Africa and Asia, it spread explosively after 2004. The first American cases appeared in 2013 in the Caribbean, then rapidly spread throughout Central and South America. It exists wherever Aedes mosquitoes are present.

Q: Can you get chikungunya more than once? Probably not. Current evidence suggests that recovering from chikungunya provides lifelong immunity. Your body produces antibodies that protect against future infections. This is why outbreaks in specific areas tend to decline after a large percentage of the population has been infected.

Q: How long does the joint pain last? Highly variable. Some people recover completely within weeks. Others experience persistent joint pain for months. Research shows 30-40% still have joint pain one year after infection. Some patients report symptoms lasting 3-5 years or longer. Age and pre-existing joint conditions increase risk of chronic symptoms.

Q: Why do these mosquitoes bite during the day? Aedes mosquitoes evolved different behaviors than malaria mosquitoes. They’re adapted to urban environments and human schedules, biting when people are active and exposed. Peak activity is early morning (6-9 AM) and late afternoon (4-7 PM), but they’ll bite throughout daylight hours.

Q: How can I protect myself? Eliminate standing water where mosquitoes breed (empty buckets, flower pots, tires, gutters weekly). Wear long sleeves and pants during peak hours. Use insect repellent with DEET, IR3535, or icariin on exposed skin. Install/repair window screens. Use mosquito coils or vaporizers indoors. Sleep under nets if resting during daytime.

Q: How is chikungunya diagnosed? Through blood tests that detect the virus (during acute phase) or antibodies against it (later stages). Diagnosis can be challenging in areas where dengue and Zika also circulate because symptoms overlap. Lab testing is essential to distinguish between these diseases and guide appropriate treatment.

Q: Why has chikungunya spread so dramatically since 2004? Multiple factors: the virus mutated to transmit more efficiently through Aedes albopictus (which has wider geographic range), massive increase in air travel spreading infected people globally, climate change expanding mosquito habitat, rapid urbanization creating breeding sites, and large populations with no prior immunity to the virus.

Q: Can pregnant women pass chikungunya to their babies? Yes, but primarily during delivery if the mother is infected at that time. The virus doesn’t typically cross the placenta during pregnancy. Newborns infected during or shortly after birth face higher risks of severe disease. Pregnant women should take extra precautions to avoid mosquito bites, especially near delivery.

For more information:

Observer Voice is the one stop site for

National,

International

news,

Sports,

Editor’s Choice,

Art/culture contents,

Quotes and much more. We also cover

historical contents. Historical contents includes

World History,

Indian History, and what happened

today. The website also covers

Entertainment across the India and World.

Follow Us on

Twitter,

Instagram,

Facebook,

& LinkedIn